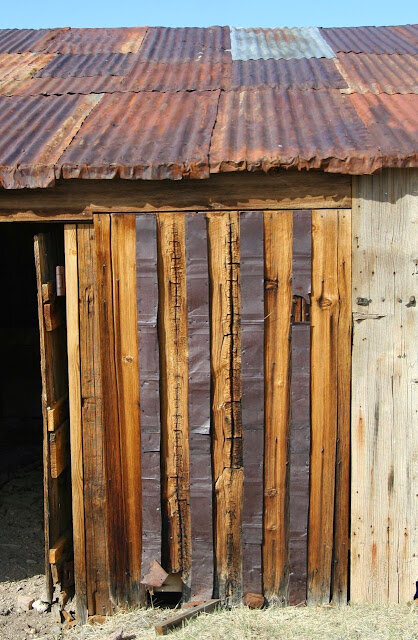

Ever since I have lived at our present home, there has been a very sad fence on the property line we share with a our neighbor. Like some mysterious archeological dig, this fence had history. Near the street, this fence line held a pretense of normalcy. However, as it progressed from the front yard to the back yard alongside our driveway, a series of unfortunate construction details ensued.

I don’t know specifically why the fence was cast on a concrete curb…I have theorized it was to keep some previous dog or rodent from digging under it. This would all be well and good if the wood that was cast into this curb, was holding up. It was not. In stark contrast to the unusually substantiality concrete curb, the wood fence above it, was precarious. “Teetering”would be a good descriptor. When it came time to purge the yard of this ailing fence, the wood fence itself would go quietly. The concrete curb was another story.

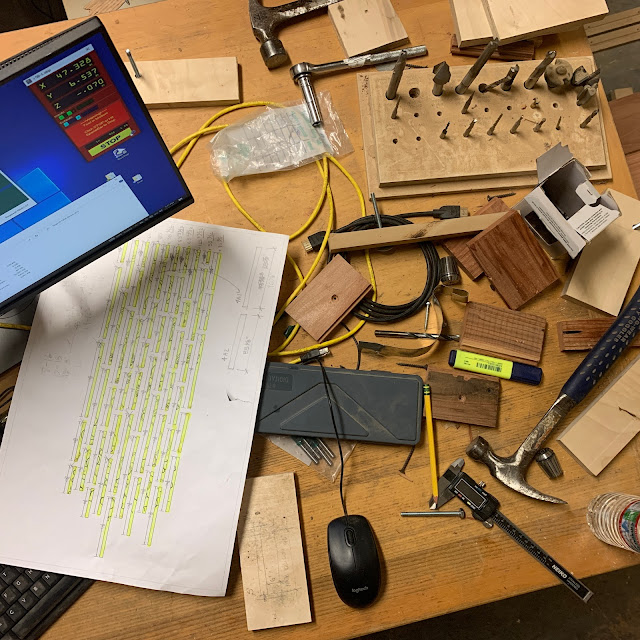

Intermittently, fence posts would penetrate this curb and descend into their shallow and insubstantial concrete footings. The post’s width was essentially the same as the curb, so everywhere there was a post, the curb would be interrupted. So much for using a concrete curb to maintain a separation of wood from soil! To make matters worse, the demolition of this fence was made so much more challenging by the existence of this curb. Removing a rotten wood fence is one thing, you can push it down. Removing a continuous concrete curb with sporadic shallow concrete post holes, is another matter. A trip to Aaction Rents to get a jackhammer is required. A digging bar is required. Ear plugs are required. A flexible back is a plus also.

If the new fence wanted to be a strong and healthy one, with even post spacings, the curb and its post holes needed to go. While typical yard work might be pruning bushes and mowing the lawn, this fence replacement felt like cruel and unusual punishment. As you might imagine, the new fence design did not have the same random post spacing as this old fence. As such, it was really impossible to avoid casting new post hole near, or partly in, old post hole. The new concrete holes often took more concrete than the old ones did.

We are now half way to the back of the property…

After the teetering-wood-fence-atop-poorly-constructed-curb experience we encounter a redwood tree. This is not your Platonic ideal of a Redwood tree. This redwood tree was a miserable redwood tree specimen. Maybe it is a misnomer to call it a tree? It might be more appropriate to say this redwood tree was a bush left over from some far more noble creature that had existed freely. A time before people came along with their appetites for fences and reduced it to the miserable creature it now was. Imagining it now, I would describe the “event” like passing an accident on the freeway. A fence had clearly had an accident with a tree. It was not clear there would be any survivors.

Moving past the tree accident we now encounter the third act. Here, whatever aspirations the fence builders had to make a straight fence, have been abandoned. More small trees arise. Whoever had worked on the fence had, at this point, clearly abandoned all hope of making it to the back property line without resorting to desperate measures. The fence bobbed and weaved around the trees. Sometimes it appeared the carpenter had needed the tree to hold up the fence. Other times it appeared the fence was being pushed over by the unruly trees. The post holes became shallower as roots complicated excavation. The unreliable tree branches became poor substitutes for footings as the fence leaned against these forms with increasing frequency as the fence terminus approached.

As awful as it was, there is something about this found chaos that excites in me the potential alchemy of a new design. This kind of work is far from the trophy projects I am guilty of wanting. On the other hand, if I was honest with myself, it is this challenge that is far more prevalent and has the reliable distinction of being the major substance of design work needed in the world. Let this be a relief. Look at how low the bar is? Witness the previous design train wreck. This is all that there is to surmount in order to call your subsequent project a success. If you simply do this, you will be a kind of healer. If you can make something that tempts beauty, the whole experience will become a kind of transcendent experience that feels reliably good.

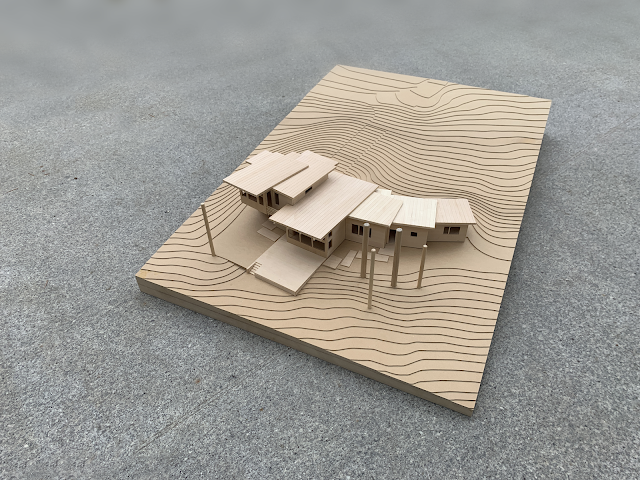

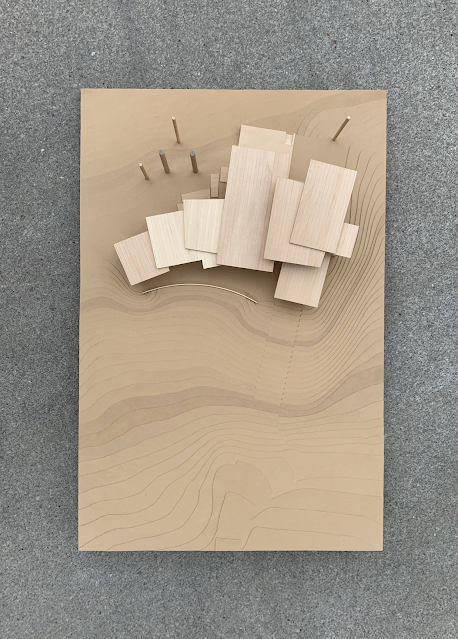

There is no better place to implement a design than in these scarred places. As an architect, I believe our ability to reshape our world can positively impact our existence. Making a shelter that fosters human inhabitants in the unkind wilderness is one of the clearest and conspicuously heroic examples of a designers craft. We have all seen the beautiful mountain retreats, cliff top homes and vineyard estates. A handsome structure ensconced in a nature setting is a compelling and lovable image. There is the potential for (excuse the pun) ground-breaking work in this setting.

New technologies can be used to harvest resources in creative new ways. It is a wonderful gift to have these kinds of projects. But there is also a escapism here that we can lose ourselves in. Are the cliff top dwelling in a design magazine, the civilized rogue of a male magazine model or the wild beauty of a cover girl, really so different? How much of what we see in these images is of any real substance? If we permit ourselves to look closely, there is often a lot less substance there than we might care to admit. This idea of remaking nature has lost some of its nobility. Yes, it is still a wonderful undertaking when done responsibly and sensitively. But let’s face it: It isn’t always done this way.

Few here in California, can reasonably give that compliment to the vast majority of our constructs. Many, including housing developments, are speculative ventures designed with an industrial ethos geared to generate income for someone who is not necessarily living there. In many ways, the fence I had in my backyard was this sort of thing. It was either built by a renter who had not stake in the outcome of the property, a landlord who was a slum lord or a homeowner who, unfortunately, did not know how to build.

Given all this, it is hard to escape the sense that good design and construction should be implemented here as much as anywhere; in the places where humans had already built but good design and care had been foresaken. Expediency had ruled the day. Let’s skip a few pedigrees and edify a rescue dog!

In many ways, California is America’s side yard. Even if someone gets a piece of land and it feels untrammeled, chances are, if one looks closer, they will see the traces of things that came before, that have not been entirely unearthed. Robinson Jeffers spoke of a “cabin in the woods under spared trees.” Every form of construction is like this; a form of destruction.

I could speak about the tired and self-evident need for some kind of sustainable design, the truism that we must, in good conscience, leave something better for our children by more being sensitive to our natural environment. Beyond this goody goody language, I believe there is something more primitive and primordial that coconspires with this more sanctimonious and hand-wringing rhetoric:

We want to generate beauty out of natural resources. That kind of sensitivity is both a coping skill and an homage. This ritual inevitably generates a kind of respect for our environment that does not need to be taught. Sensitivity is incidentally learned on the way toward goals that are of a more immediate, and perhaps more self-serving, nature. It’s okay. It might even be healthy.

We can forget about all this when we are afraid. Afraid that we aren’t going to survive if we spend our time making beautiful things. Afraid that there is not enough time or energy to be spent on such endeavors. All of this is perfectly understandable and equally sad. We also know that living in fear, is no way to live.

“What you can do or think you can do, begin it. For boldness has magic, power, and genius in it.” -Goethe

I myself am certainly no exception to this ethic of expediency. I have done, and will do, many things to “just get them done” and I am grateful to my partner Lisbet and my children for being patient with me through this fence project. It was clearly about more than just putting up a barrier and I know there were moments when it competed for my time with other more social activities.

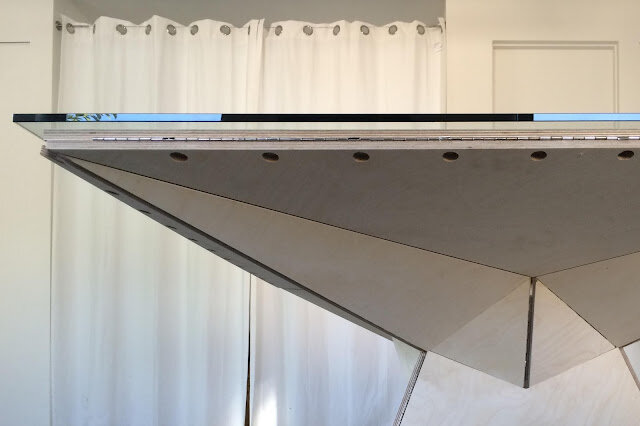

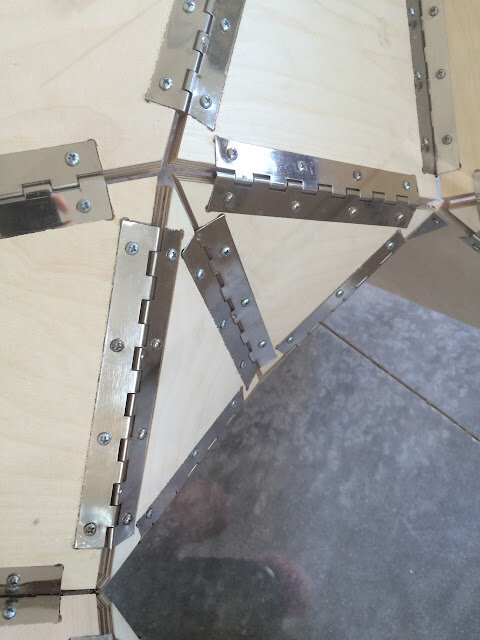

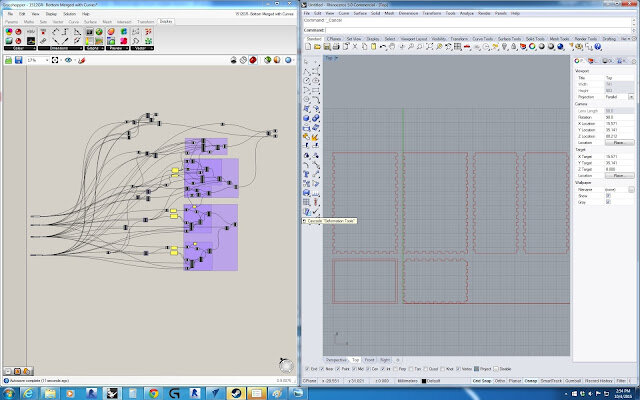

The fence I built left a lot of room for improvement, but the shortcomings were more the outcome of pushing myself to make something I had not made before and not the shortcomings associated with a rushed process that I was familiar with. I look forward to sharing that fence design in the next post.